Caution

This material appeared in the Better Scientific Software An Introduction to Software Licensing lesson, but has not yet been incorporated into the INTERSECT version.

License Compatibility

- In practice, most software is a combined work of some kind

- Multiple packages with (potentially) different licenses (e.g. main package and dependencies)

- Do the license terms allow the packages to be distributed (or even used) together?

- Is the combined work considered a derived work?

- Different licenses have different concepts of what constitutes a derived work and how derivatives may or must be licensed

- Example: strong copyleft considers linking to produce a derived work, and requires derivatives be distributed under the same license as the original

- There are different interpretations of what licenses are compatible

- Little litigation so far

- Most significant concerns tend to be about distribution of software

- Larger projects starting to pay more attention to his

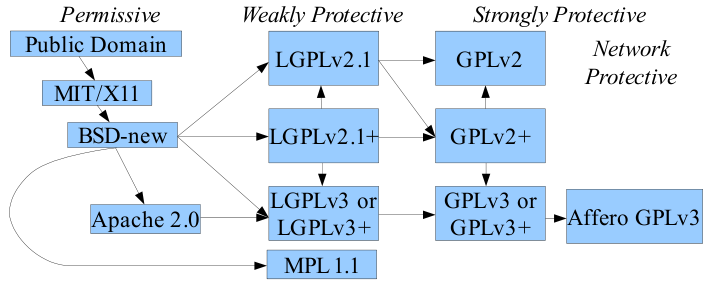

License Compatibility in Pictures

One view of license compatibility between common FOSS software licenses. The arrows denote a one directional compatibility, therefore better compatibility on the left side than on the right side. By David A. Wheeler - http://www.dwheeler.com/essays/floss-license-slide.html, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41060008 via https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/License_compatibility

Strategies for Reducing License Compatibility Concerns

- Don’t distribute other software packages as part of yours

- Especially if you’re distributing binaries

- If you need to modify other software, try to upstream changes or ship only patches instead

- Consider the licenses of your immediate software ecosystem

- Your dependencies

- Other software yours is likely to be used with

- Think about how your software interacts with other packages in the ecosystem

- Recall earlier discussion of the different definitions of “derived work” for different licenses

- Consider the licensing practices of the community or target audience

- Permissive licenses tend to have fewer compatibility problems

- Consider relicensing your software

- More on this coming up

Some Related Matters

Software Licenses Can be Changed

- You may start out using one license for your code and later discover unanticipated problems

- Or maybe your goals change

But changing licenses is not necessarily easy

- (Generally) each and every contributor to a code holds a copyright interest in it

- Each and every contributor must be contacted and agree to the relicensing

- In practice, different institutions may have different ideas of “due diligence”

- Keep good records of contributors; try to keep them current

- Contributor license agreements (CLAs) and contribution transfer agreements (CTAs) can simplify this

- But present different challenges (see upcoming slide)

Changing License Example #1

- Organization owns copyright for several software packages

- Licensed LGPL

- Authorship agreements were signed at time copyright was asserted

- Several packages contained third-party source files

- A variety of licenses

- Many packages received contributions from other authors since initial copyright assertion

- Many prospective (particularly industry) customers were wary of LGPL

- Decision was made to relicense to BSD

Changing License Example #1 (continued)

- Contributions were deemed to be substantive or “bug fix”

- This was a distinction suggested by a lawyer, every situation will be different

- All third-party software was judged to have a compatible or incompatible license

- Most packages were eventually relicensed, a few were not

- A contributor agreement was adopted after this

- Proved challenging in practice and is largely not used.

- Considered building an agreement into pull-request template

- Not clear if that is enforceable

- Often people do not have the ability to agree on behalf of their employer

Changing License Example #2

- Another case of moving to a less restrictive license

- Effort was made to obtain agreement from all 400+ contributors

- This was successful, except one contributor had passed away

- His contribution was removed from the code base

- This was a more careful and exhaustive effort than the first example

- Not implying it is better or worse

Accepting Code Contributions

- Code contributions are implicitly offered under the current license

- Some projects require a contributor agreement

- Contributor license agreement (CLA) defines the terms between the contributor and the maintainers of the software

- Contributor transfer agreement (CTA) transfers copyright ownership from contributor to maintainers

- Developer Certificate of Origin (DCO) has been proposed as an alternative to CLAs

- Developer asserts that they have permission to submit the code. Not a signed legal contract

- Why?

- Clarify or make explicit terms of contribution (awareness by contributor)

- Obtain additional rights, e.g., relicensing, patents, etc.

- Ensure “clear title” to make the contribution

- Why not?

- Creates “barriers to entry” – may discourage potential contributors

- Legal agreements that may require official review and signature

- Experience: Lost funding for a project because lawyers wouldn’t agree to terms of a CLA

- See Resources slide for several viewpoints